The narrator recalls how he became a writer. It turned out simply and even unintentionally. Now it seems to the narrator that he was always a writer, only "without a seal."

In early childhood, the nanny called the storyteller a “chatterbox”. He has preserved the memories of early infancy - toys, a birch branch by the image, “babble of incomprehensible prayer”, scraps of old songs sung by the nanny.

Everything for the boy was alive - living toothy saws and shiny axes chopped living in the yard, crying with tar and wood shavings. The broom "ran around the yard for dust, froze in the snow and even cried." A sex brush similar to a cat on a stick was punished - put in a corner, and the child comforted her.

Everything seemed alive, everything told me fairy tales - oh, what wonderful!

Thickets of burdocks and nettles in the garden seemed to the narrator as a forest, where real wolves live. He lay in the thicket, they closed above his head, and the result was a green sky with "birds" - butterflies and ladybirds.

Once a man with a scythe came into the garden and mowed down the entire "forest". When the narrator asked if the man had taken the braid from death, he looked at him with “terrible eyes” and growled: “I am now death myself!” The boy got scared, screamed, and he was carried away from the garden. This was his first, most terrible encounter with death.

The narrator remembers the first years at school, the old teacher Anna Dmitrievna Vertes. She spoke other languages, which is why the boy considered her a werewolf and was very afraid.

What “werewolf” means - I knew from carpenters. She is not like any baptized person, and therefore speaks such as sorcerers.

Then the boy found out about the "Babel of Babel", and decided that Anna Dmitrievna was building the Tower of Babel, and her tongues were mixed. He asked the teacher if she was scared and how many languages she had. She laughed for a long time, but her tongue turned out to be one.

Then the narrator met a beautiful girl Anichka Dyachkova. She taught him to dance, and kept asking to tell tales. The boy learned from the carpenters many tales, not always decent, which Anichka liked very much. During this occupation Anna Dmitrievna found them and scolded them for a long time. Anichka did not pester the storyteller anymore.

A little later, older girls learned about the boy’s ability to tell tales. They put him on his knees, gave him sweets and listened. Sometimes Anna Dmitrievna came up and also listened. The boy had a lot to tell. The people in the big yard where he lived were changing. They came from all the provinces with their tales and songs, each with his own talk. For the constant chatter of the narrator they nicknamed the "Roman speaker."

It was, so to speak, the preliterate century in the history of my writing. “Written” soon came after him.

In the third grade, the narrator was carried away by Jules Verne and wrote a satirical poem about the teachers' journey to the moon. The poem was a great success, and the poet was punished.

Then came the era of essays. The narrator is too free, according to the teacher, to reveal topics, for which he was left in the second year. This went to the boy only for the benefit: he got to the new vocabulary, which did not impede the flight of fantasy. Until now, the narrator remembers him with gratitude.

Then came the third period - the narrator moved on to "his own." He spent the summer before the eighth grade "on a remote rivulet, on fishing." He fished in a pool at the idle mill, in which a deaf old man lived. This vacation made such a strong impression on the narrator that, while preparing for the exams for the matriculation certificate, he put off all matters and wrote the story “At the Mill”.

I saw my pool, a mill, a broken dam, clay cliffs, rowan berries showered with brushes of berries, grandfather ... Alive, they came and took it.

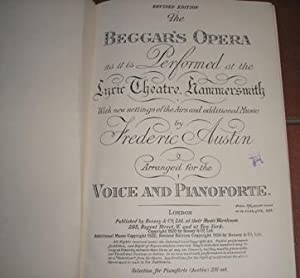

What to do with his composition, the narrator did not know. In his family and among acquaintances, there were almost no intelligent people, and he had not yet read the newspapers, considering himself superior to this. Finally, the narrator recalled the sign "Russian Review", which he saw on the way to school.

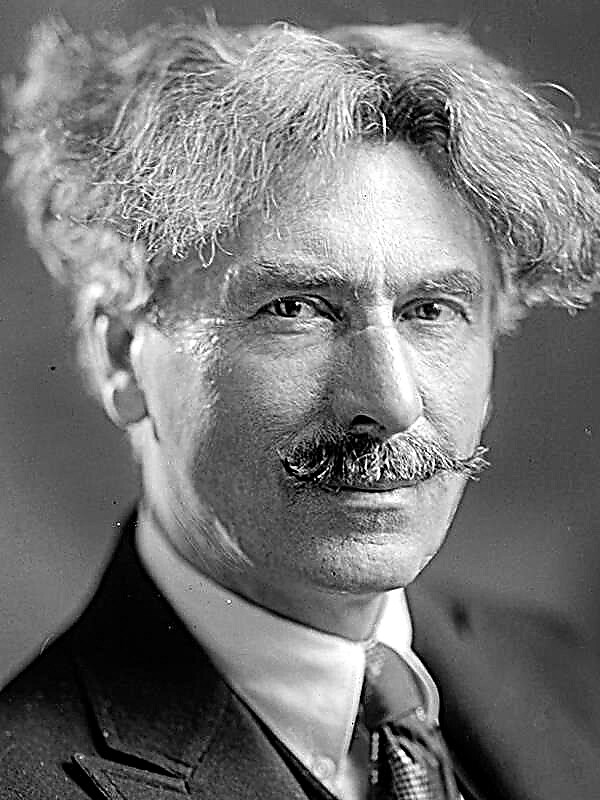

After hesitating, the narrator went to the editorial office and got an appointment with the editor-in-chief, a solid, professorial-looking gentleman with graying curls. He took a notebook with a story and ordered to come in a couple of months. Then the publication of the story was postponed for another two months, the narrator decided that nothing would come of it, and was captured by another.

The storyteller received a letter from Russkoye Obozreniye with a request to “drop by to talk” only the following March, already as a student.The editor said that he liked the story, and it was published, and then advised me to write more.

I did not say a word, left in the fog. And soon he forgot again. And I didn’t think at all that I became a writer.

The storyteller received a copy of the journal with his essay in July, was happy for two days and forgot again until he received another invitation from the editor. He handed the aspiring writer a huge fee for him and talked for a long time about the founder of the magazine.

The narrator felt that behind all this “there is something great and sacred, unknown to me, unusually important”, to which he only touched. For the first time, he felt himself different, and knew that he had to "learn a lot, read, peer and think" - prepare to become a real writer.