The hero of the novel - Fedor Konstantinovich Godunov-Cherdyntsev, a Russian emigrant, the son of a famous entomologist, an offspring of an aristocratic family - lives in poverty in Berlin in the second half of the 1920s, earning private lessons and publishing nostalgic twelve stories about childhood in Russia in Russian newspapers. He feels a huge literary potential in himself, he is bored of emigrant gatherings, his only idol among his contemporaries is the poet Koncheev. With him, he leads a relentless internal dialogue "in the language of imagination." Godunov-Cherdyntsev, strong, healthy, young, full of happy forebodings, and his life is not overshadowed by either poverty or the uncertainty of the future. He constantly catches in the landscape, in the scrap of the tram conversation, in his dreams the signs of future happiness, which for him consists of love and creative self-realization.

The affair begins with a rally: inviting Cherdyntsev to visit, emigrant Alexander Yakovlevich Chernyshevsky (a Jewish Jew, he took this pseudonym out of respect for the idol of the intelligentsia, lives with his wife Alexandra Yakovlevna, his son recently shot himself after a strange, angry “menage, and trois”) promises to show him an enthusiastic review of the newly published Cherdyntsevsky book. The review turns out to be an article from an old Berlin newspaper - an article about a completely different story. The next meeting at the Chernyshevsky’s, at which the editor of the emigrant newspaper journalist Vasiliev promises everyone to get acquainted with the new talent, turns out to be a farce: the attention of the audience, including Koncheev, is offered a philosophical play by a Russian German by the name of Bach, and this play turns out to be a collection of heavyweight curiosities. Kind Bach does not notice that all present are choking on laughter. To crown it all, Cherdyntsev again did not dare to speak with Koncheev, and their conversation, full of explanations in mutual respect and literary similarity, turns out to be a game of imagination. But in this first chapter, which tells of a chain of ridiculous failures and errors, the plot of the hero’s future happiness. Here the cross-cutting theme “Gift” arises - the theme of keys: moving to a new apartment, Cherdyntsev forgot the keys to it in the mac, and went out in a raincoat. In the same chapter, the fiction writer Romanov invites Cherdyntsev to another emigre salon, to a certain Margarita Lvovna, who has Russian youth; the name of Zina Merz (future beloved hero) flickers, but he does not respond to the first hint of fate, and his meeting with an ideal woman intended for him alone is postponed until the third chapter.

In the second, Cherdyntsev takes in Berlin the mother who came to him from Paris. His landlady, Frau Stoby, found a free room for her. Mother and son recall Cherdyntsev Sr., the father of a hero who went missing in his last expedition, somewhere in Central Asia. Mother still hopes that he is alive. The son, who was looking for a hero for a long time for his first serious book, thinks of writing a biography of his father and recalls his paradise childhood - excursions with his father around the estate, catching butterflies, reading old magazines, solving sketches, sweet lessons - but he feels that these are scattered notes and dreams the book does not loom: he is too close, intimately remembers his father, and therefore unable to objectify his image and write about him as a scientist and traveler. Moreover, in the story of his wanderings, the son is too poetic and dreamy, but he wants scientific rigor. Material is too close to him at the same time, and at times alien. And the external impetus for the cessation of work is the transfer of Cherdyntsev to a new apartment.Frau Stoboi found herself a more reliable, monetary and well-meaning guest: Cherdyntsev's idleness and his writing embarrassed her. Cherdyntsev chose the apartment of Marianna Nikolaevna and Boris Ivanovich Shchegolevs not because he liked this couple (an elderly bourgeois and a peppy anti-Semite with a Moscow reprimand and Moscow banquet jokes): he was attracted by a pretty girl’s dress, as if inadvertently thrown in one of rooms. This time he guessed the call of fate, even though the dress did not belong to Zina Merz, the daughter of Marianna Nikolaevna from her first marriage, but to her friend, who brought her blue air toilet to the remake.

The acquaintance of Cherdyntsev with Zina, who has long been in absentia in love with him in verse, is the theme of the third chapter. They have many common acquaintances, but fate postponed the rapprochement of the heroes until a favorable moment. Zina is sarcastic, witty, well-read, thin, she is terribly annoyed by her maternal stepfather (her father is a Jew, the first husband of Marianna Nikolaevna was a musical, thoughtful, lonely man). She categorically opposes Shchegolev and mother to learn something about her relationship with Cherdyntsev. She confines herself to walking with him around Berlin, where everything meets their happiness, resonates with him; long languid kisses follow, but nothing more. Unresolved passion, the feeling of nearing but slowing happiness, the joy of health and strength, the liberated talent - all this makes Cherdyntsev finally begin serious work, and, by coincidence, the life becomes Chernyshevsky. Cherdyntsev was carried away by the figure of Chernyshevsky not by the consonance of his last name with his own and not even completely opposite of Chernyshevsky’s biography of his own, but as a result of a long search for an answer to the question tormenting him: why in post-revolutionary Russia everything became so gray, boring and monotonous? He turns to the famous era of the 60s, searching for the culprit, but discovers in Chernyshevsky’s life the very break, a crack that did not allow him to build his life harmoniously, clearly and harmoniously. This breakdown was reflected in the spiritual development of all subsequent generations, poisoned by the deceptive simplicity of cheap, flat pragmatism.

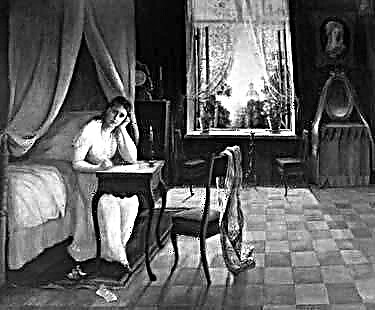

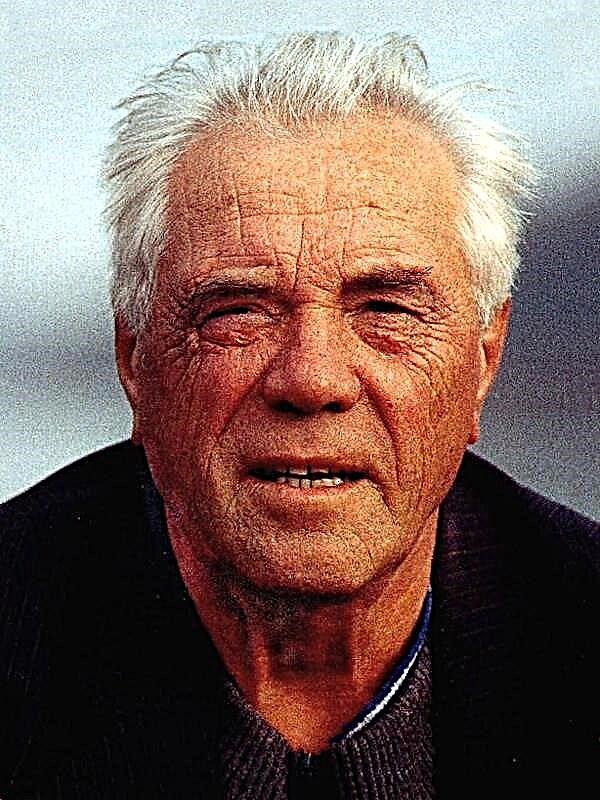

The “Life of Chernyshevsky”, which both Cherdyntsev and Nabokov made a lot of enemies of and made a scandal in emigration (the book was first published without this chapter), is dedicated to the debunking of Russian materialism, “rational egoism”, an attempt to live by reason, and not by intuition, not artistic intuition. Mocking Chernyshevsky’s aesthetics, his idyllic utopias, his naive economic teachings, Cherdyntsev warmly sympathizes with him as a person when he describes his love for his wife, suffering in exile, heroic attempts to return to literature and public life after liberation ... There is that very same in Chernyshevsky’s blood " a piece of pus ”, about which he spoke in his dying delirium: inability to organically fit into the world, awkwardness, physical weakness, and most importantly - ignoring the external charms of the world, the desire to reduce everything to a race, benefit, primitive ... This seemingly pragmatic, but in fact a deeply speculative, abstract approach kept Chernyshevsky from living all the time, teasing him with the hope of the possibility of social reorganization, while no social reorganization can and should not occupy an artist who seeks in the course of fate, in the development of history, in his own and others' lives, above all the highest aesthetic meaning, the pattern of hints and coincidences. This chapter is written with all the splendor of Nabokov’s irony and erudition. In the fifth chapter, all of Cherdyntsev’s dreams come true: his book was published with the assistance of the good man Bach, over whose play he was rolling with laughter. She was praised by the very Koncheev, about whom our hero dreamed of friendship.Finally, intimacy with Zina is possible: her mother and stepfather leave Berlin (stepfather got a seat), and Godunov-Cherdyntsev and Zina Merz remain together. Full of jubilant happiness, this chapter is clouded only by the story of the death of Alexander Yakovlevich Chernyshevsky, who died, not believing in a future life. “There is nothing,” he says before his death, listening to the splash of water behind the curtained windows. “It's just as clear as it is raining.” And on the street at this time the sun is shining, and the Chernyshevsky neighbor is watering flowers on the balcony.

The theme of the keys pops up in the fifth chapter: Cherdyntsev left his keys to the apartment in the room, Marianna Nikolaevna took away the keys of Zina, and the lovers find themselves on the street after an almost wedding dinner. However, most likely in the Grunewald forest they will be no worse. And Cherdyntsev’s love for Zina - a love that came close to her happy resolution, but this permission is hidden from us - does not need keys and a roof.